Invisible Man

In researching book challenges I often tell people that you can’t really predict what will set people off. There are what I call the three S problem: swearing, sex, and sexual orientation (+gender identity but that doesn’t fit the alliteration). A book with any of these in a library or a school classroom is certainly more likely to get challenged than other books. But I’ve seen some pretty crazy ones — my favorite currently is a Catholic who objected to a comic book’s depiction of Joan of Arc as a lesbian because she was his personal saint. Sometimes the challenge comes against a classic of American literature helping to bring public attention and, sometimes, ridicule on the school. In 2013, the Randolph County Board of Education ran full speed into a censorship controversy when it removed Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. It all started with a summer reading list.

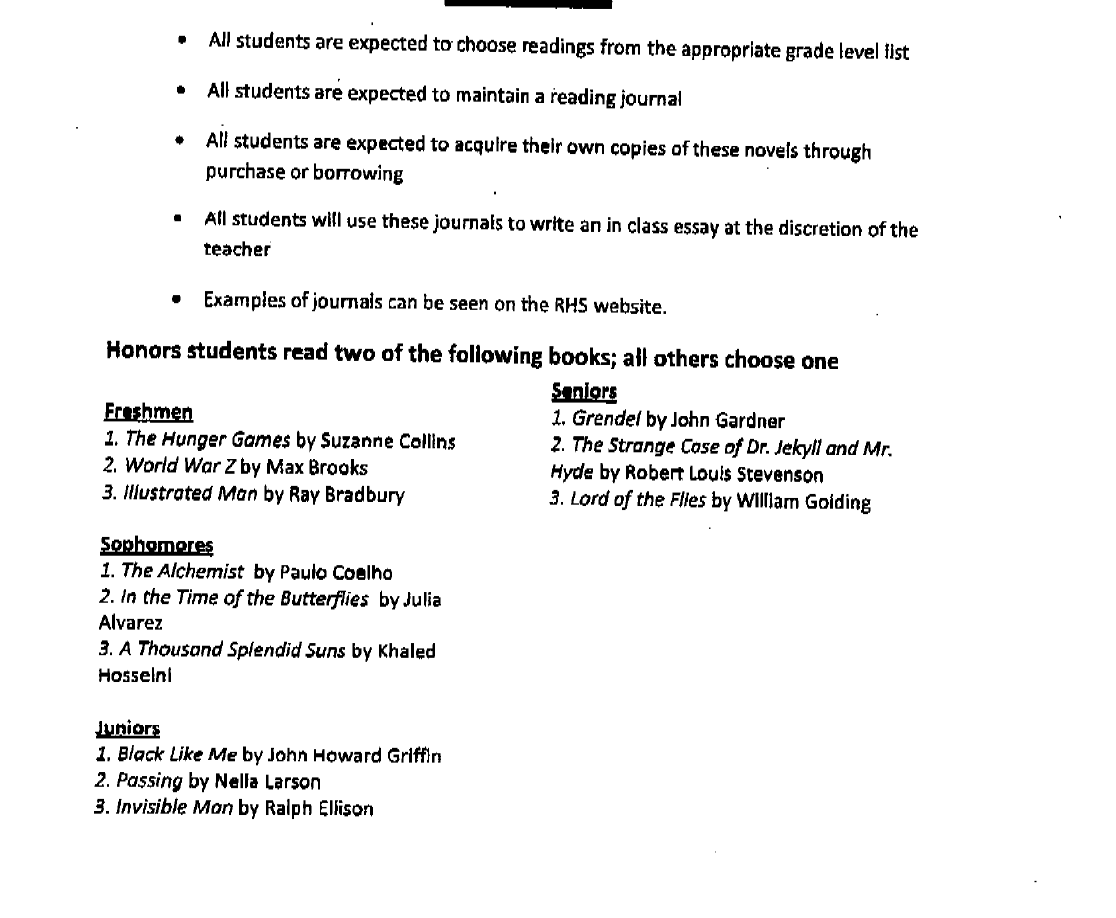

Students were to read one book, two if they were in honors, and keep a journal for the summer. I imagine that the English department did not think much about the inclusion of Invisible Man as it is a major work of American literature and, as it would note in the reconsideration process, the subject of many questions on AP exams. In other disputes I sometimes see emails from teachers who note that they had assigned the book in question for years and never once had it questioned but it only takes one challenger. In Randolph County, one parent complained loudly when their child brought the book home.

The two quotes illustrate the core of the challenge. The book is filthy and discusses the narrator’s sexual exploits. Specifically they highlight three chapters, 2, 3, and 24, as the “worst.” Excerpts of this material were provided to support the claim that “[t]his novel is not so innocent.” The lack of innocence amazes the challenger, it is obvious that the people who adopted it must not even have bothered to read the book as it is clearly inappropriate. The lack of warning is particularly unacceptable. Parents don’t have time to read every single book assigned, they trust the experts. But a warning wasn’t actually what the challenger wanted. The school committee voted to retain Invisible Man but also noted that in the future a warning would be added to the sheet for any book that had swearing or sex. This was insufficient for the challenger who appealed the decision arguing that one warning wouldn’t do any good and parents would likely never see it before their child got the book. So lack of a warning was terrible but a warning was insufficient. This kind of logic runs through book challenges, especially in English curriculum. After all, this parent was responsible and stopped their child before it was read. Other parents are not capable of being as good a parent, either because they are over-worked or because they are under-educated. Challengers rarely conceive of a world where a parent would actually want their child to read the book in question. “You must respect all religions and point of views when it comes to the parents and what they feel is age appropriate for their young children to read, without their knowledge.” In other words, this challenger asserts their right to control all access to the book to protect all students.

Noting the extensive literary praise and merit of the book, the reconsideration committee retained Invisible Man. On the off-chance that more parents than the one challenger would be concerned, the committee instituted a number of transparency rules. In particular, the list would now have a synopsis of the books, a disclaimer noting any possible objectionable materials (drugs, sex, swearing, etc.), and they would be ordered in terms of increasing difficulty to allow students to make a decision based on their reading level. As noted above, this was insufficient to the challenger who seemed amazed that any rational group of adults could possibly read Invisible Man and support it in a reading list or the library. So they appealed to the School Board.

To date, I’ve collected about 60 challenges related to English curriculum. When a school board gets involved it typically sides with the school in my experience. After all, the school has made a professional judgment, one that in the case of school wide reading lists came from the entire English department, and boards tend to support their institution. This is more likely when no child has to actually read the book in question. This is not always the case, however, as boards are also elected and come from a diverse background. Some may have professional educational experience but many don’t and it is possible that the members themselves have relatively little education. As elected officials, board members may feel pressure from the public, or a particularly energetic subset of the public, and side with them.

Things went badly before the Randolph County Board of Education. As Emily Knox explores in her Book Banning in 21st-Century America, the Board had little knowledge of the book. One member told Knox that many of the members hadn’t read it and he had only read the first few chapters. They were working off the excerpts provided by the challenger. Despite this failure to read it, they voted 5-2 to remove the book from the school because it was “a hard read” with one saying that he “didn’t find any literary value” in it. The Board member who spoke to Knox worried that having swear words in a book assigned for class was an invitation for students to think swearing is ok. While removals are probably not the norm, they happen. What made this case unusual is the immediate public backlash. Beginning with a local paper, the story quickly spread far and wide (here’s the LA Times story as an example.) Social media helped spread the story. The exposure was almost certainly helped by the literary standing of the novel and most of the news stories noted the awards won by the book. The Board began receiving emails and phone calls from around the world attacking the decision.

The Board held another meeting on the 25 September 2013, having removed it on 16 September, and the discussion changed markedly. Knox notes that the District’s attorney expressed reservations about the vote both for procedural (she wasn’t sure a removal vote was legally on the agenda) and constitutional reasons. The school administration also laid out its review process in more depth. Ultimately the Board voted 6-1 to reinstate the book. The Board member Knox interviewed frankly admitted that they acted from a place of ignorance and further reflection led him to reconsider. Of course, being called, in essence, an illiterate bumpkin by major newspapers and getting a stream of hostile messages in that vein didn’t help. Few people like to have their decisions criticized and the Board members were all happy to vote initially without any real knowledge. It was only the public exposure that corrected the situation.

One lesson from this challenge was that schools can’t really please everyone. The challenger here had the power to prevent her child access without a problem. Then the school went further to make that easier by adding information the reading list but that wasn’t enough for the challenger. Typically resisting such efforts are made easier by the extreme nature of the claim. While we might reasonably agree that parents should have control over their children’s reading, there is never a basis for allowing one parent’s objections to control another child’s activities. The process, however, can be arbitrary at times and here the Board, reacting to a few excerpts without any broader knowledge of the book, removed it reasoning that it was too filthy to provide. At this point public pressure was the best option. A lawsuit might have won — and I can’t stress enough how vague the constitutional doctrine in this area really is — but lawsuits require resources and time. The public exposure served to shame the Board into reversing course is less than two weeks. This is one reason why I will never join the ranks of people who hate social media. Sure it has terrible aspects but it was social media that helped spread this story far and wide. Sadly, we don’t know how often these kinds of censorship decisions are made behind closed doors.