Remembering When Judy Blume Was "Porn"

My censorship research has drawn me to a lot of fun archives and I’ve decided to start sharing some interesting finds from time to time. This is one of my favorites from the American Library Association Archive at the University of Illinois-Champaign. Sadly, Covid prevented me from actually visiting but the archivists were great about scanning a ton of material for me and one piece was a collection of complaints made about the great Judy Blume and her 1970s novels for adolescents and teens. Today we hear accusations that everything is “porn” from book banners so I thought it would be interesting to highlight an example of Blume as porn back in 1981.

Book challenges - the request to have a book removed from, relocated, or restricted within a library or school - largely arose in the 1970s due to two key forces. First, the demise of obscenity for books. Through the 1960s it was still common for prose novels to be targeted as obscene but due to obscenity law changes this ended in the 1970s; also, the market for actual porn exploded so no one cared about occasional sex in books. Second, young adult literature experienced the birth of contemporary realism. Where a lot of teen books were moralistic, sanitized tales before, this new round of pioneering authors had the audacious idea to write books about the lives that kids actually lived. This included swearing, drug use, alcohol, sex, and so on. Judy Blume, to me at least, is the founder of this movement and she was enormously successful. Shockingly, kids liked to read stories about experiences they recognized. And for that her books were some of the most targeted by book banners for decades. Here is one example I found from Green Bay, Wisconsin, in 1981.

Green Bay Press-Gazette, 25 March 1981.

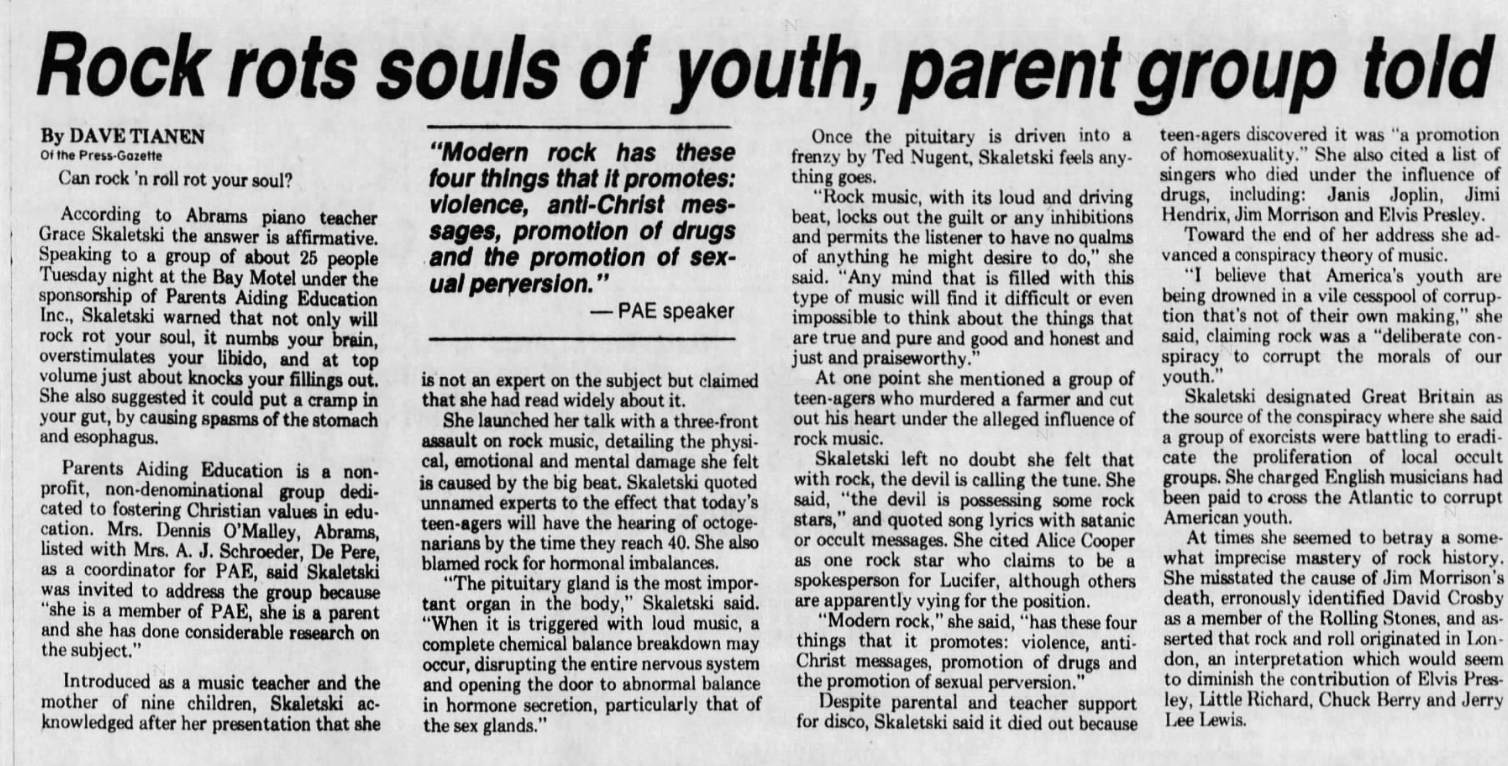

Described by the local press as a group of about 50 parents, Parents Aiding Education (PAE) appears to be a fairly standard local Christian Right group of the era. Above is one of their campaigns targeting the dangers of rock music - I had to post the whole story, it’s just that good. PAE hated Blume’s books. They admitted she was popular: “There is almost a national mania for these books. Dell Publishing Company … reports having printed over six million copies of her books … Library shelves are stacked with multiple copies of everything Miss Blume has written, and it is almost impossible to fine the books not checked out.” While this might be cause for celebration for champions of youth literacy, PAE was aghast. Blume’s books were dangerous “because the values they espouse are not reflective of Judeo-Christian values but rather are secular-humanistic in character.” I’ll just note two of the four books attacked, the other two were Deenie and Then Again, Maybe I Won’t.

First up is Blume’s groundbreaking Are You There God? It’s Me Margaret. Margaret is 11 and talks about boys, bras, and first periods with her friends. But to the PAE she is “shallow” and “self-centered” with a “petty attitude toward life.” She dares to think bad thoughts about her mother, for example, and to a Christian Right group few things are worse than a child who dares to question authority. The key attack on Margaret is the fact that it focuses on menstruation. To shame based cultures, like those of the Christian Right, a girl menstruating is something to be afraid of because it means sex is too close and she has to be controlled to avoid her worth being ruined by losing her virginity. Blume’s highlight of the girls discussions of puberty and periods is thus dangerous, it brings what should be shameful and hidden into the limelight. And it leads to dangerous events like looking at a Playboy magazine and going to a “boy, girl” party where kids may be kissing (gasp!, clutches pearls).

Second is Blume’s Forever. Forever pushed contemporary realism in young adult literature even further by tackling the subject of teen sex directly. To the PAE this was a dangerous promotion of teen sexuality. The blurb above notes both that she goes to Planned Parenthood to get on birth control - later PAE complains “There is no presentation of the hazards of the birth control pill for teens” because one classic Christian Right tactic is to lie to kids about birth control. And Blume even mentions that Katherine would get an abortion if her birth control fails. The PAE presents all of Blume’s books as directed at “stimulating the young readers sexually and affecting their attitudes toward sex” and Forever “is the culmination of this pre-conditioning.” To Christian Right groups, teens will not have sex if they don’t read about it. And Blume goes even further, according to the PAE, because “there is no warning of the moral and social jeopardy into which a young girl places herself” when she loses her virginity. To these folks, purity in girls is essential and sex is a danger they must be protected from. The idea of a girl like Katherine making an educated, mature decision to have sex is dangerous. Instead ignorance and fear must be the only guide for teens.

In this PAE was your typical Christian Right group and honestly you could easily swap out the titles and the complaints are the same today from book banners. They equated Blume’s popularity with junk food and “[j]ust as young people need adult care and supervision in the area of nutrition, so too do they need our care in selecting suitable reading material.” What came of this? Well PAE focused only on the Green Bay area and at least one school district in De Pere immediately removed all of the books while others kept them, and still some didn’t even have them (a classic example of self-censorship given the popularity of the books). PAE fades immediately from the local press suggesting it was a sort of flash in the pan protest group. But its arguments give us a window into the censorship activity of Christian Right groups of the time.

In a Los Angeles Times interview (18 October 1981), Blume provided a response to the censors: “I see a tendency for adults who can’t control everything that’s happening in their lives to try to control their children’s lives. One place to begin is by controlling your child’s reading. But you can’t control another human being’s life, another human being’s thoughts. Even if you removed all objectionable (to censors) books from the schools and libraries, you can’t stop children from thinking about things written about in those books. The fear that children’s values will change because they are exposed to other values isn’t valid if there is communication between parent and child. Let children read whatever they want and then talk about it with them. If parents and kids can talk together, we won’t have as much censorship because we won’t have as much fear.”

Source: American Library Association Archive, University of Illinois-Champaign. Coll. 6/1/6 Office for Intellectual Freedom Collection. Box 40, Blume, Judy - cases, 1978-94. I would usually post the full material but the archive restricted my ability to share the scans so I have opted for extensive quotes in this post.