Changes in Censorship Tactics

It’s National Library Week and so that means a lot of commentary driven by the American Library Association’s State of the Libraries Report. The part that gets the most attention is the list of most challenge books for 2022. The data is compiled by the ALA’s Office of Intellectual Freedom (OIF) and is based upon reports made to the OIF by librarians, teachers, and others. This is still likely to be an undercount, perhaps a dramatic one, but even this limited data speaks to the dramatic escalation of censorship. The list of most challenged books for 2022 is exactly what I expected to see.

Usually I spend most of this annual post focusing on the books but honestly there isn’t much to say about this list. If you asked the challengers, they would say they are driven by one thing: “porn.” But, of course, none of these books have anything that looks like “porn.” To these challengers, however, any mention of sex or sexuality makes it porn and thus dangerous. So sure, nearly all of these books depict and discuss sex. As sex is an important part of most people’s lives, it would be odd for literature not to have it. To these censors, however, sex is treated as something dirty and evil; if you inform teens about sex, they will have sex. An idiotic belief system but it is what it is. Unsurprisingly, in the nitty gritty of the challenges you discover that even their claims about “porn” is little more than window dressing as they challenge books with zero sex for simply having stories of Black and queer existence. The list has an example: Flamer. Flamer, which I discussed here, has no sex but supposedly it is explicit. My interest, here, is more focused on process and the data I found most illuminating in the OIF material.

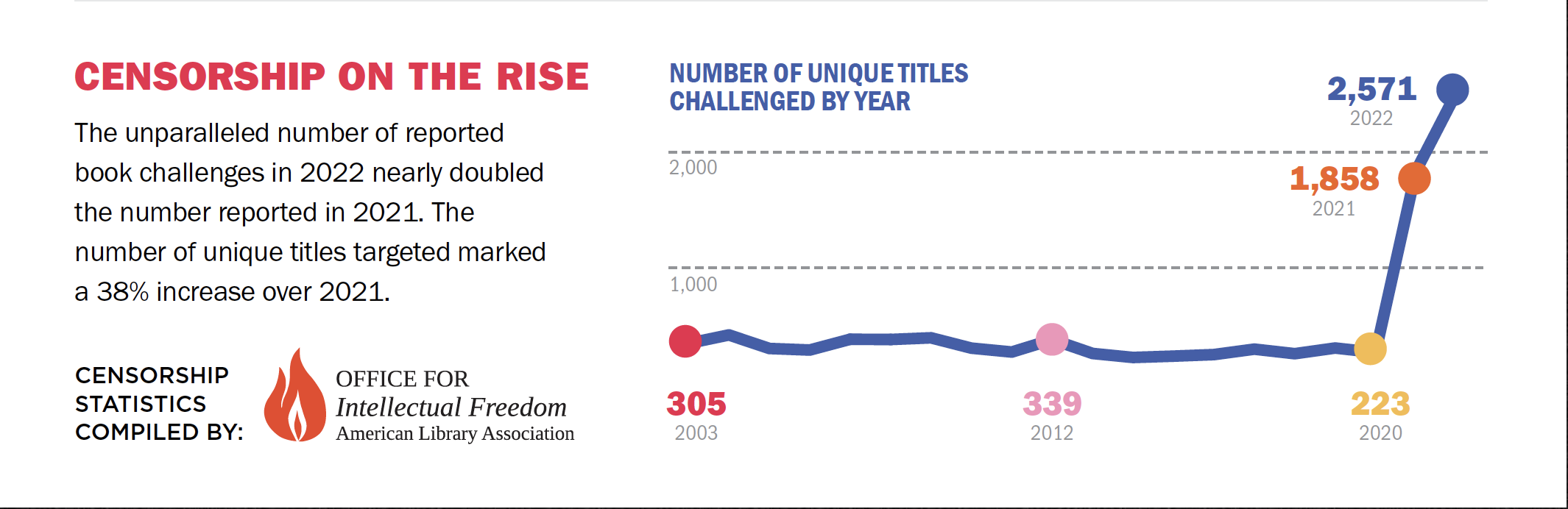

This chart summarizes changes in the process of challenges nicely. I’ve collected hundreds of challenge documents and even more archival material going back decades on censorship. Book challenges - which are attempts to have material removed, restricted, or relocated within schools and/or libraries - tended to have a pretty standard story for a long time. The stories usually fell into one of two common themes. First, a person goes to the library and sees something on the shelf that they are shocked by. It might be a title, or a cover of two boys kissing, or a religion they don’t like. Second, and probably the most common, a child brings a book home from the library or classroom that the parent is shocked by. Now the norm was for the challenger to read the book before challenging it. This was not always done, of course, but the weight of the evidence is that more often than not challengers read and engaged with the book. Many of the arguments were still silly, such as there are swear words in the book, but at times they offered quite detailed analysis rejecting the material. This isn’t to say that their arguments were convincing but I can respect people who do the work. The chart, however, shows how much things have changed.

Doing the work of actually engaging with a book and explaining why it should be removed, say from a class reading list, takes effort. This is why unique titles were so consistently low for a long time. But the number of books has exploded precisely because the process has changed. Now we have large networks of Christian Right activists putting together huge lists of books that they deem objectionable because they include sex, Black stories, mentions of abortion, queer people, swearing, or pretty much anything else that Christian Right activists deem evil. They do not read these books. The lists just point to excerpts found through searches of ebooks and then cut and pasted so that no context appears. At times this might be as little as a few lines, at times a page or two. These lists are circulated through activists networks and members go to libraries and schools submitting hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of book challenges at once. Many times they do not even bother to find out if the book is in the institution, the list is all they need. And they celebrate their refusal to read the material. They echo an argument that I’ve seen since at least the late 1800s: that there can never be good to redeem an evil book. So a single episode of sex, or the presence of queer people, or a story of racism pollutes any value the book can ever have.

This old argument was rejected by most of society in the 1960s in favor of a right to read. Now, sadly, institutions are caving to these attacks in larger numbers. Some are doing so out of exhaustion of constant attacks, others because school and library board elections have put pro-censorship officials in place. The real weight, however, has come in states like Florida and Texas where new laws have been adopted creating the serious risk of crushing financial liability as well as threats of criminal charges from frivolous legal claims; claims that could never hold up in court, but would bury teachers and librarians in legal fees. Here in Utah, many schools resisted the first wave of censorship but then a new law was passed to make the threats much stronger, even though the law had no real effect, but the threats were sufficient scaring schools to purge large numbers of books.

Sadly, this is the new normal of book challenges. I had naively thought this level of hate would gradually wear down as much of it was tied to the early pandemic - that is a longer story - but I’ve been proven wrong. They are a small and extreme minority but the energy required is very low since larger groups have put together the lists and all they have to do is file the challenges. The harassment of libraries and schools is unlikely to end anytime soon, sadly.