Censorship Class: The Great Comic Book Panic

After looking at film censorship and the Hayes Code last week, this week we explored the comic book panic of the 1940s and ‘50s. This is fun because there are always a few hard core comic readers in a class but thanks to the last twenty years of film nearly everyone has some grasp of comic book structure and content. The fear over this medium both seemed to amuse students but also to be unsurprising, in part because of what we have studied to date (I assume).

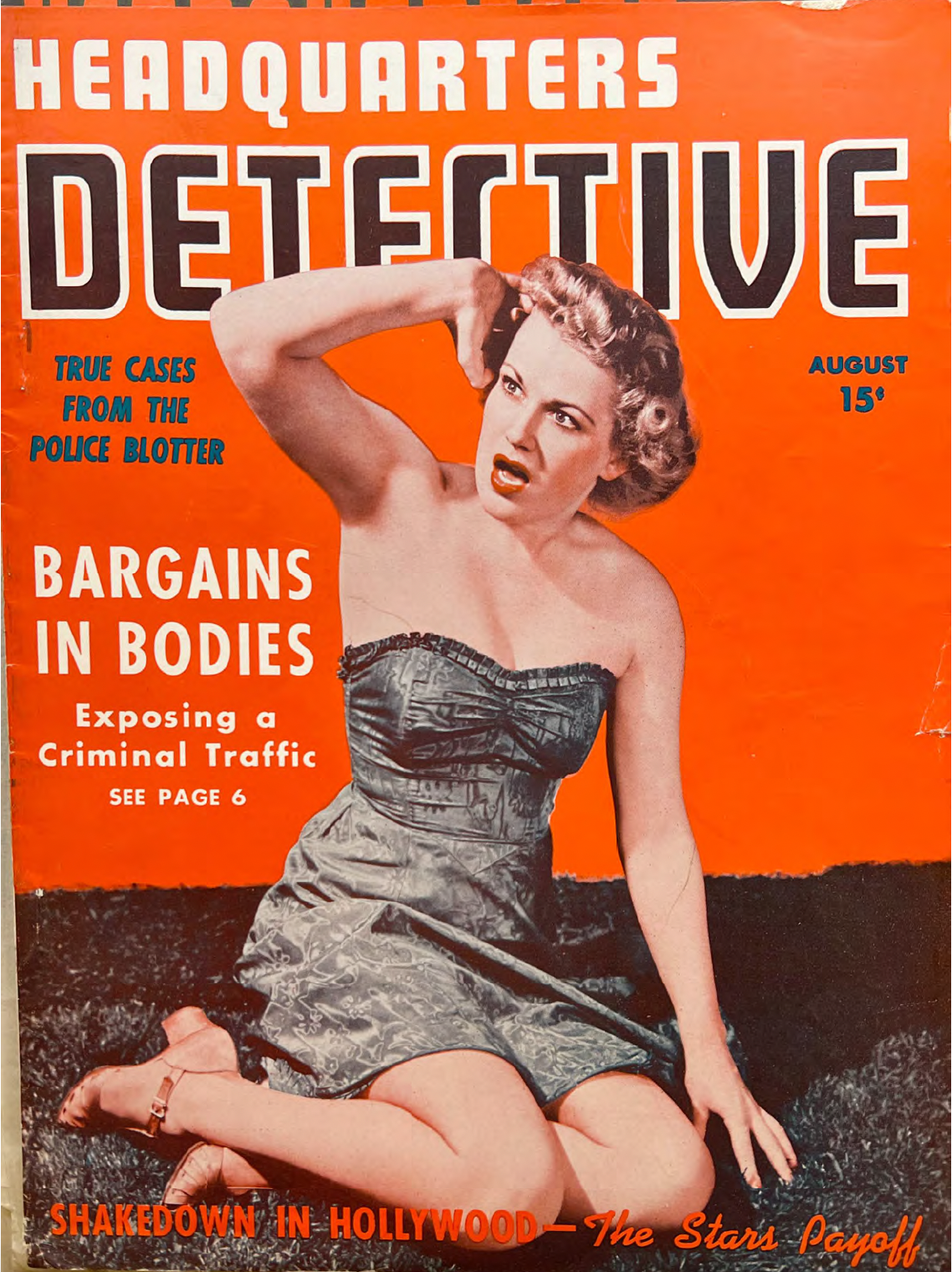

Headquarters Detective, August 1940.

Before the comics, I began with Winters v. NY (1948) an oft-overlooked milestone in censorship law. Winters involved punishing a newsstand dealer for selling magazines “principally made up of criminal news, police reports, or accounts of criminal deeds.” Here’s an example I provided to my students of such magazines (that I found in Morris Ernst’s papers.) These kinds of laws actually have a long history with many states prohibiting publication of crime material since the late 1800s. The justification was that such material, even if true, encouraged a scandalous vision of the law and enticed readers, particularly children, to commit crimes. While this kind of justification was common at the time, New York was odd in that it applied its ban to all readers, not just minors. SCOTUS proved deeply skeptical of this decision and the state’s broader argument. Particularly important, it announced that something being entertaining did not disqualify it from being protected speech: “The line between the informing and the entertaining is too elusive for the protection” of speech and press rights. If this sounds obvious today, well at the time there was a whole school of thought, touched on in last week’s film discussion, that entertainment media wasn’t really speech. This declaration began to shift censorship and obscenity law much more towards a pro-speech position. After that, the decision is a fairly standard argument that the statute is far too broad to serve the interest claimed and it is too vague for any seller to be legitimately punished under it.

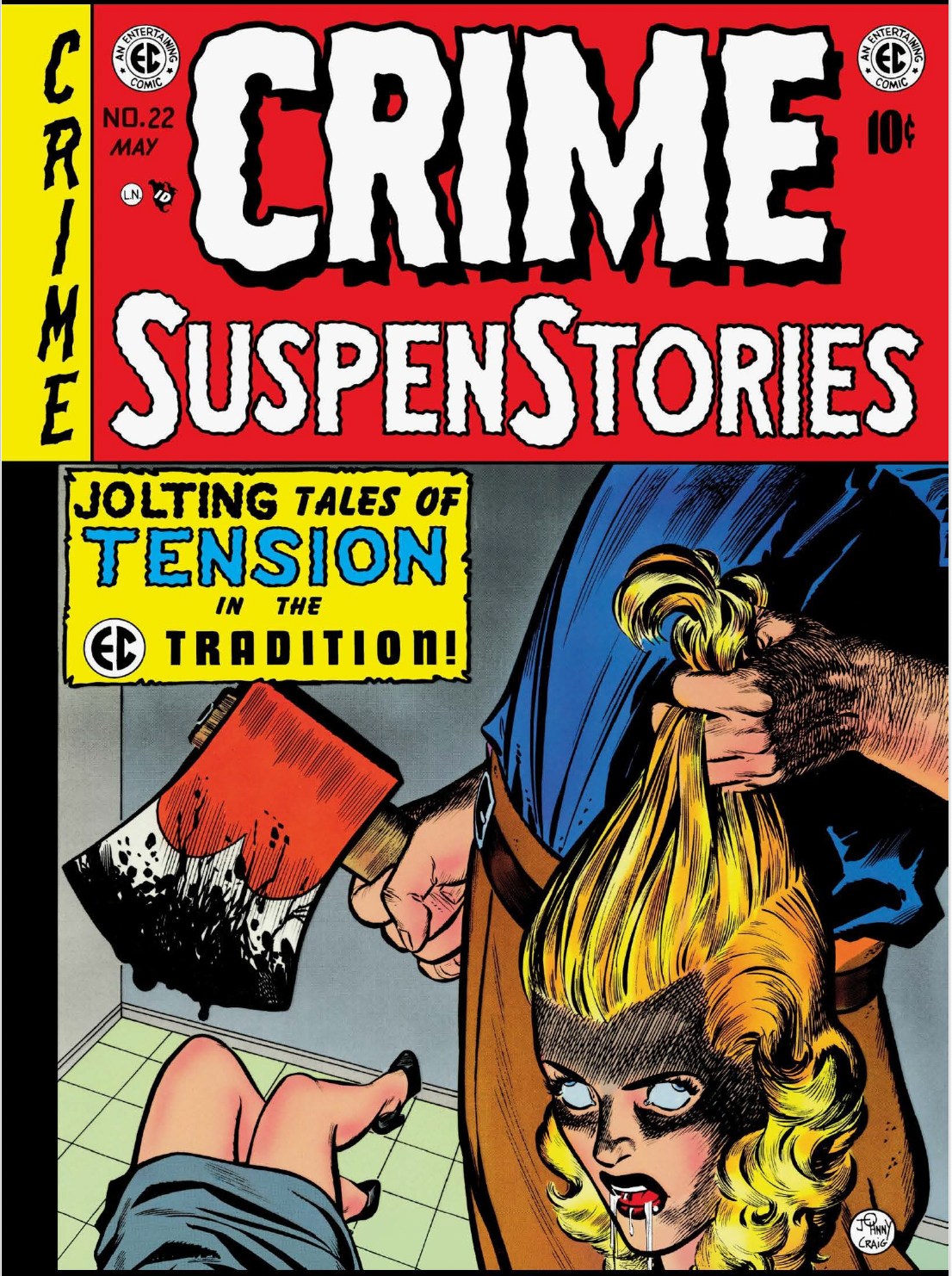

Crime SuspenStories #22

Comics took prime place quickly. Beginning in the newspaper funnies and then emerging in the Great Depression into a longer form of sequential art and story, represented by the classic early issues of Superman, Batman, and Captain America, to name only a few. But after World War II, the anxiety over youth culture, (supposed) juvenile delinquency, and the state of the family in the face of the dangerous Red Menace led many to worry that comics were contributing to the decline of America. No one represents the comics panic better than Dr. Fredrich Wertham a leading psychiatrist of the period. He is most famous for Seduction of the Innocent (1954) but I provided his first draft for students to take a look. We had a lot of fun poking at the silly use of anecdotes in his activism, how he selected on the dependent variable for all of his evidence of the supposed nature of comics causing criminal behavior, and his various arguments about crime. But students particularly loved the discussion found in his book about how comics, especially Batman and Robin, turn kids gay. (I only realize now that I totally forgot to inform them that even his anecdotes were often partially false and misleading as well). What I was fascinated by is that a student raised the different reaction they felt to Wertham’s scientific presentation over prior weeks of moralistic preaching. They suggested that they still hated his argument but approached it more carefully because of the expertise and authority. This led to a fun discussion of the limitations of his actual evidence - and I’m even more annoyed I forgot to mention the falsification now - and I got to discuss that even at this time the scientific evidence didn’t support Wertham’s argument about comics causing crime. As the Massachusetts legislature declared in 1956, it might not be scientifically proven but common sense says it must matter. Another censorship trope that I see expressed often.

I gave them a few different EC Comics stories that were noted in Wertham’s work to take a look at. One interesting takeaway was that most of these crime stories adhered to the core morality: the villains were punished ultimately, even if ironically. So if good triumphed over evil, why were comics a problem? The discussion came around to the idea that comics were seen as a uniquely childlike medium. The assumption, perhaps more accurate in 1950s America than at times later, was that the audience was primarily pre-adolescent children and, thus, they couldn’t be trusted to recognize the correct interpretation. Of particular concern was the violent imagery of crime and horror comics that could be understood by even pre-literate children.

The panic Wertham fed blew up into regular state and federal legislative hearings served primarily as a position taking effort by politicians wanting to be seen as actively fighting the dangerous comics in the papers and on new TVs but not actually do much. But like many such moral panics, they whipped up such attention and energy that the comics industry decided they would learn from the Hays Code and adopt an industry censorship regime in the form of the Comics Code with the most significant being the 1954 Code. In fact, some of the Comics Code was clearly lifted from the Hollywood regime and focused on similar issues such as law and order is always victorious. But the Code is famous for its total prohibition on horror comics. The industry simply decided to sacrifice an entire genre to protect its broader interests. Students were particularly amused by the language around costumes and images prohibiting “suggestive” clothing. As modern comics have been defined by idiotic, mostly female, skimpy costumes, this was a fun digression.

Ultimately, the Code worked perfectly in that the panic was defused. But censorship regimes must be prepared to adapt to changing times, politics, and audiences to stay in power. I introduced the students to the Spider-Man story “Green Goblin Reborn!” 1971 story that went to press without a Code stamp, the first time that had happened. You see the story depicted a character using drugs and fighting addiction, forbidden by the original Code but requested specifically by the Nixon administration to combat the rise in teen drug use. The Code was actually revised shortly after to now allow drug and alcohol abuse to be shown so long as it is in a negative light. As society continued to shift, the Code would move in other ways before beginning its death in 2001, when Marvel left, and ending in 2011, when DC pulled the plug. But in its heyday the Code was an impressively successful internal censorship regime that flattened the art form for decades.

Next week my students have their first research week where I try to give them time to get started on their various projects. Then we turn to one of the central issues in my research: smutty literature in the 1950s and ‘60s.