Censorship Class: Smutty Literature

After examining the comic book panic, my censorship class turned to one of my favorite topics: smutty literature in the 1950s and ‘60s. Obscenity and censorship has always had an obsession with sex. The boom in postwar paperback book sales opened up an entire new market for smutty literature that censors tried to block. Some of this was serious work of avant garde artists, like Allen Ginsburg’s Howl, and some of it was material deemed inartistic and for the masses, like Tereska Torrès’s Women’s Barracks. So this is one of my favorite areas to explore.

It is framed against the groundbreaking Roth v. U.S. (1957) decision. Lawyers and courts had wrestled with the idea of obscenity for about a hundred years at this point but had almost never framed the issue as one of free speech. Gradually a group of dissident lawyers and judges began to alter this reality by noting the definition of obscenity directly implicated speech because where we draw a line on the legality of a book, magazine, film, etc. limits the content that consumers have access to. Roth would be the success of this movement when Justice William Brennan declared, based on some seriously weak evidence, that obscenity is not speech but that the definition of obscenity is heavily wrapped up in free speech doctrine. A key declaration was that “sex and obscenity are not synonymous” because for many censors sex was treated as inherently obscene. Instead, Brennan’s formulation centered obscenity law on an unhealthy interest in sex: “whether to the average person, applying contemporary community standards, the dominant theme of the material taken as a whole appeals to prurient interest.” Brennan and most members of the Court believed that it had to draw a line between legitimate literature and art and irredeemable smut. It would take Brennan 17 years to realize that no such line was possible, but that is a separate discussion.

Grove Press edition, 1959.

I focused the class in part on what I call the smutty trilogy. Immediately after Roth, Barney Rosset of Grove Press wanted to push the envelope and he arranged to print an unabridged copy of D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928). Lawrence was a major figure in modern English literature but a number of his books faced obscenity charges in the U.S. and U.K. In particular Lady Chatterley’s Lover because of its depiction of an affair across British class lines, the explicit sexual episodes, and the dirty words he used. The book had been perhaps the leading example of literary obscenity for thirty years but it was actually easy to legalize after Roth. Mostly because Lawrence’s reputation as a major author helped legitimize the book as something more than smutty literature. In 1959, Grove Press won a major case finding it not obscene and the book faced no real opposition at that point. It was also cleared of obscenity in a much more involved 1960 British trial. This only set the stage for the real battle.

Grove Press edition, 1961.

Tropic of Cancer was sort of the bastard sibling of Lady Chatterly’s Lover in that it enjoyed significantly less literary respect both for the novel and its author, though it had some. But Rosset loved it and decided to bring out a full edition as well. This one was met with fierce resistance. It was a bridge too far for the censors. A police chief from the Chicago area was warned at a conference about the filthy book about to hit shelves and he called other police chiefs in the suburbs to warn them. Most of them then sent officers out to bookstores, drug stores, and newsstands to warn the sellers. They pointed to page 5 of the book and made it clear that if the book wasn’t pulled they would face charges, pretty much all pulled it from the shelves. All told, Rosset fought something like 60 obscenity cases around the country. Most appellate courts, but not all, held it protected. (SCOTUS ultimately found it not obscene in a summary opinion). For example, the Massachussets high court worried that “Much in modern art, literature, and music is likely to seem ugly and thoroughly objectionable to those who have different standards of taste” and “competent critics entertain … the view that Tropic has great literary merit despite its repulsive features.” This issue of merit became increasingly important to obscenity law in the 1960s. In fact, the final book of the smutty trilogy, Fanny Hill, would be constitutionalized in a famous - or infamous - opinion that embraced a broad requirement that obscenity be “utterly without redeeming social value.” (Though this was not supported by a majority of the Court.)

Legalizing Tropic of Cancer was seen by many pro-censorship folks as the beginning of the end of literary obscenity. Students seemed interested in a letter I found from the National Office of Decent Literature (NODL) written to one of the first state judges to find Tropic not obscene. The NODL complained that taking merit into account would mean “the literary critic or the social scientist would displace the average man.” A healthy distrust of experts ran through this critique. Allowing Tropic was just another step to the complete destruction of obscenity and letting people read or watch what they want, oh the horrors. And to some extent they were correct.

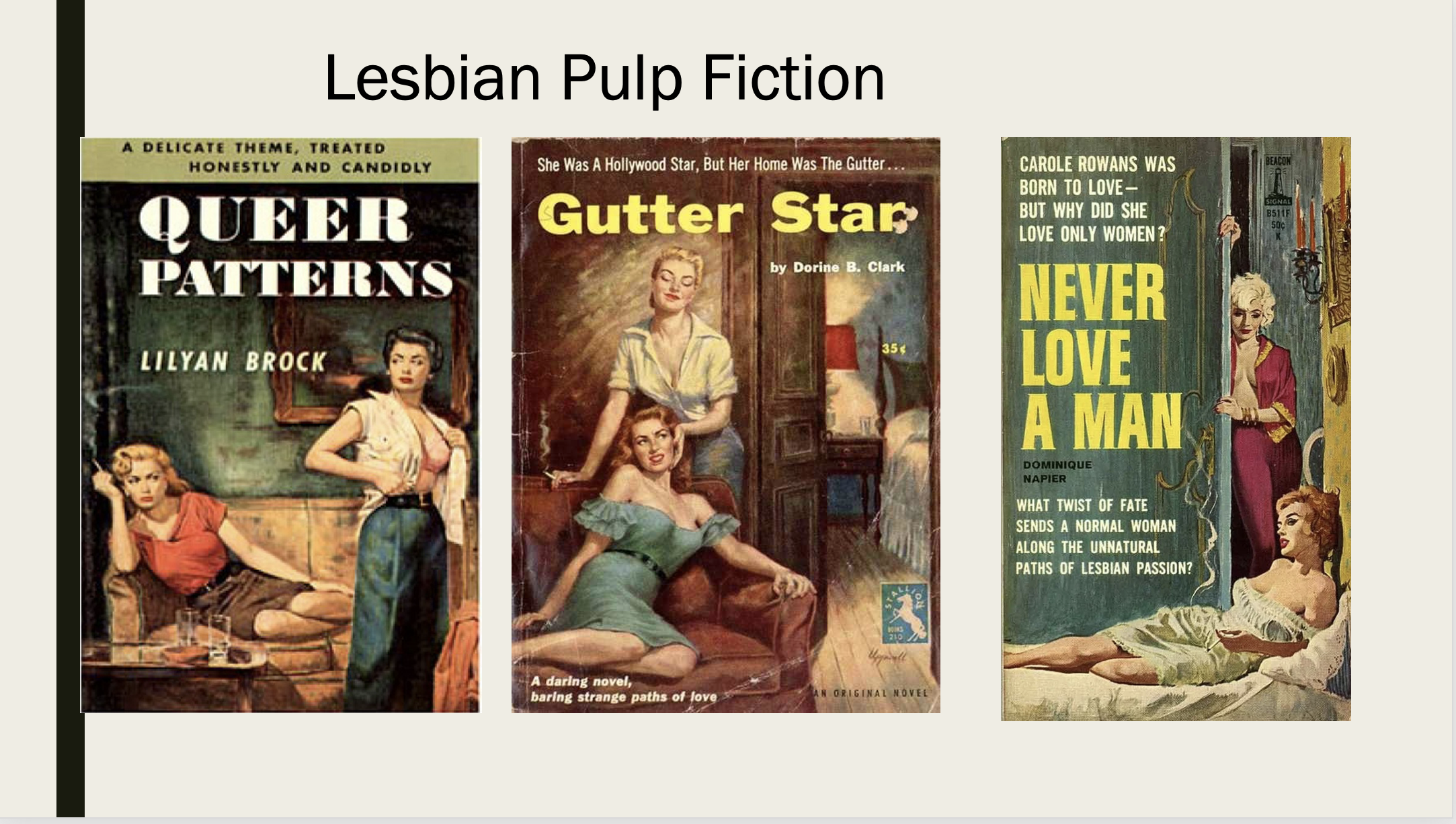

One of my favorite lecture slides.

We closed with a look at the battles over pulp fiction and lesbian pulp in particular. As students are usually unaware, Autostraddle has a fun look at examples. Lesbian pulp fiction is fascinating because it used the taboo idea of gay women to titillate mostly straight men (much as “lesbian” porn does today). But it also provided queer girls and women of the era many of their first opportunities to explore their identity. Censors targeted these books heavily convinced they destroyed community morality. Here’s a collection of complaints made by censors in Salt Lake City over one such novel.

Ultimately the story of smutty literature in the 1960s is that it did in fact represent the end of literary obscenity. Sure, legally prose novels can be obscene in theory - and there is an entire movement today trying to bring it back into vogue - but in reality by the early 1970s there was simply no longer any political will or interest. Partly, this is because society simply had trouble buying that reading about sex or violence was all that big a deal. Partly, it was the shift in obscenity to consider merit and how taking a page out of context was legally untenable. Mostly, however, it was about the marketplace. The 1970s saw the mainstreaming of hardcore pornography and smutty literature just was not on any censors target sheet anymore.

Next week we turn to the demise of the Hays Code and freeing film (mostly).