Censorship Class: Tipper Gore and the Dangers of Porn Rock

I had to follow up the week exploring comedy and the FCC with the music wars of the 1980s and ‘90s. Music had long been a source of controversy in the U.S. around the questions of race, sex, and drugs. Think of the absurdity of Elvis being accused of corrupting kids with his sexy hip shakes or how at the tail end of the 1960s it was rock music’s fault that American youth were trying more drugs. The absurdity reached new heights when Tipper Gore bought her daughter Prince’s now-classic album Purple Rain (1984). Tipper recounted being disturbed by song “Darling Nikki” because it dared to make a reference to masturbation. This outrageous bit of smut launched a movement to censor music but only music that white upper class activists didn’t like.

Tipper got together with friends, all of whom were wives of powerful politicians or rich men (or both), to form the Parents Music Resource Council (PMRC). The PMRC attempted to walk a common line in controversial material battles. They denied that they were engaged in censorship because the ultimate PMRC demand was for a warning label and this just makes it easier for consumers to know that some songs are deeply filthy. The problem is that this demand was also directed at limiting the content that they abhorred. In her book Raising PG Kids in an X-Rated Society, Tipper embraced this narrative double talk: “No one wants to take sex out of music, but the amount of explicit descriptions of sex currently being marketed to youngsters must be reconsidered.” So she didn’t want to take sex out but she wanted less sex in. The goal was to create industry censorship by threatening sales. And only partially. No where in Gore’s book or activism was sexism, violence, sex, and alcohol/drug abuse in country music mentioned. That genre got a pass because, one presumes, it represents good old fashioned (white) American values.

Of course ratings are always about censorship. Or at least that has long been my argument. Many of my students disagree, though. They often are more inclined to see it in terms of the movies, as informational but not really all that impactful. I tend to focus on the inherent subjectivity of such ratings systems, how they reflect the tastes of the raters more than any conception of public interest or harm. For example, the original proposal for the PMRC ratings included things like O for Occult References and that’s about the dumbest shit ever. As we took a look at the “Filthy Fifteen” the subjectivity becomes pretty evident. Some of these songs being included is absurd. Like Twisted Sister’s “We’re Not Gonna Take It.” If you listen to this song there is nothing objectionable to it; no swearing, sex, devil references, anything. But it ended up on the list because of the music video depicting a kid rebelling against his parents. Sure there is “violence” in some sense but it is cartoony and ridiculous. It is the idea of teenage rebellion that cannot be allowed. But as we spent much of our time discussing, a lot of this is in metaphor and what kid is even going to notice? Such as Sheena Easton’s “Sugar Walls” where sure any adult of reasonable intelligence is going to get the reference but for a teen I suspect some effort is required.

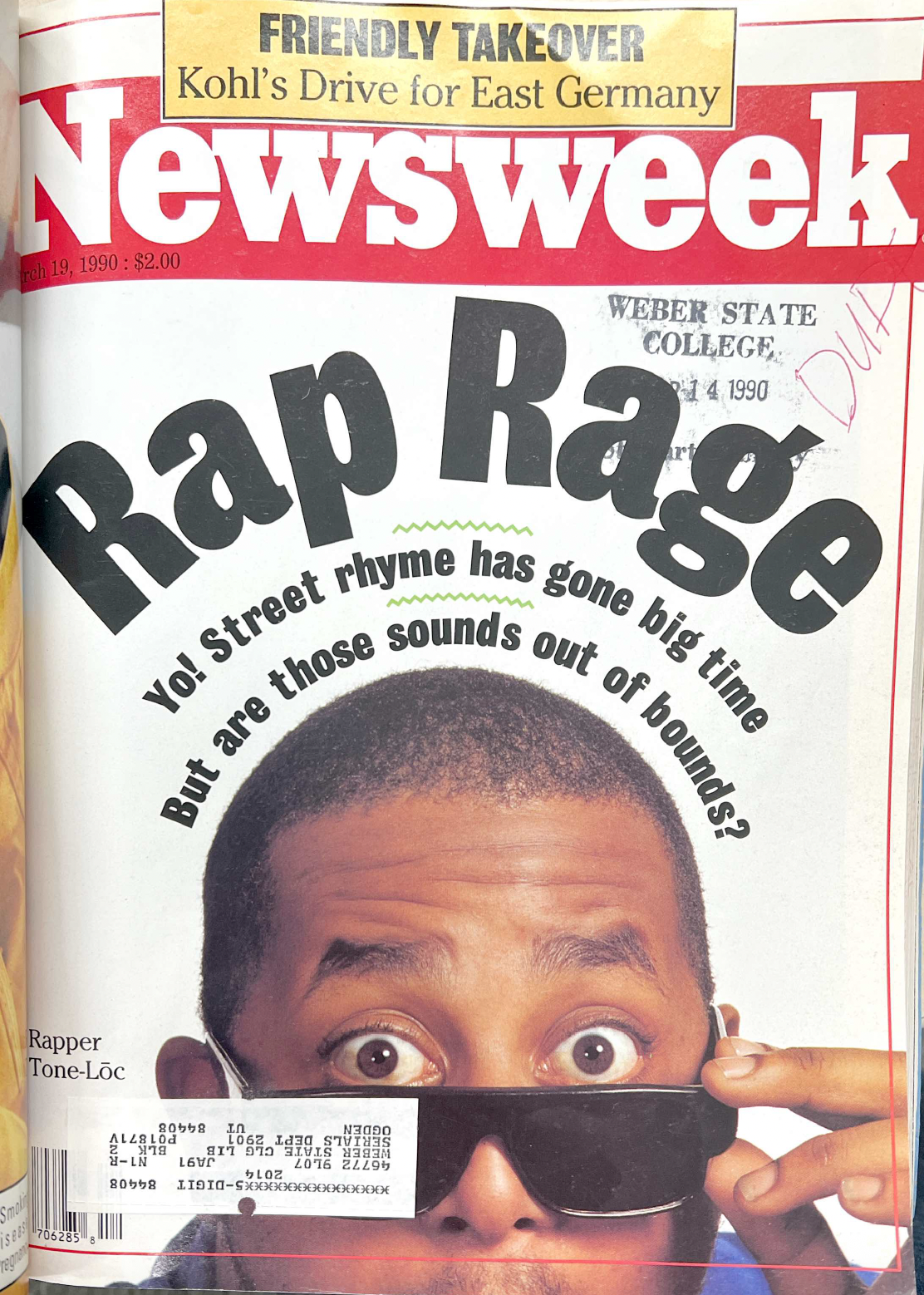

Tipper Gore largely went quiet on the music issue by the time rap came to center stage of the 1990s. I gave my students a mixture of silly moral panic pieces of the age, such as the Newsweek cover story above, that all basically summed to: rap is just noise with no point. As a white kid in the Seattle suburbs at the time I ingested a ton of this argument, it was everywhere. And as my students noted, it was driven by racism. Once suburban white kids bought albums, censors got concerned. Not because NWA was noise without a message but because it had a message that they disliked. NWA wrote about what they lived and exposed white suburban kids to a gritty reality of racism and police violence that they were lucky enough never to experience.

And that is the fear of censors. The worry that the message of the censored will get out and have a real world effect. Silencing the message is the project.